There has been much written about Hadrian’s wall over the years. Gildas was the first to write about it in or around 560AD but already a lot had been forgotten and his descriptions are quite muddled. There follows a brief synopsis but what I want to concentrate on is the plants and their colonisation of the area.

Undoubtedly the most famous wall in the Britain it was, as the name suggests, built under the orders of Emperor Hadrian, in 122AD. It was however campaigns of Julius Agricola which had pushed the Roman influence to the far north of Scotland by 84AD. He even sent ships further north still and reached the Orkneys but his gains were not maintained and much of Scotland was subsequently abandoned and so when Hadrian visited he decided to fortify a line from the Tyne to the Solway.

The seventy three mile wall took just six years to construct. Initially some of it was stone and the western section was a turf bank. This bank was subsequently replaced with stone. There is also a large ditch called a Vallum which is three metres deep with parallel mounds along the edges and which follows the line of the wall on the south side. After Hadrian’s death in 138AD the next Emperor, Antonius Pius, decided to build another wall further north between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde, known as the Antonine Wall. This was shorter than Hadrian’s Wall at just thirty nine miles but it had more forts. Construction began in 142 AD and took twelve years to complete. It is mainly comprised of an earth bank formed from turfs. It was abandoned shortly after Pius’ departure and Hadrian’s Wall marked the northern edge of Roman influence.

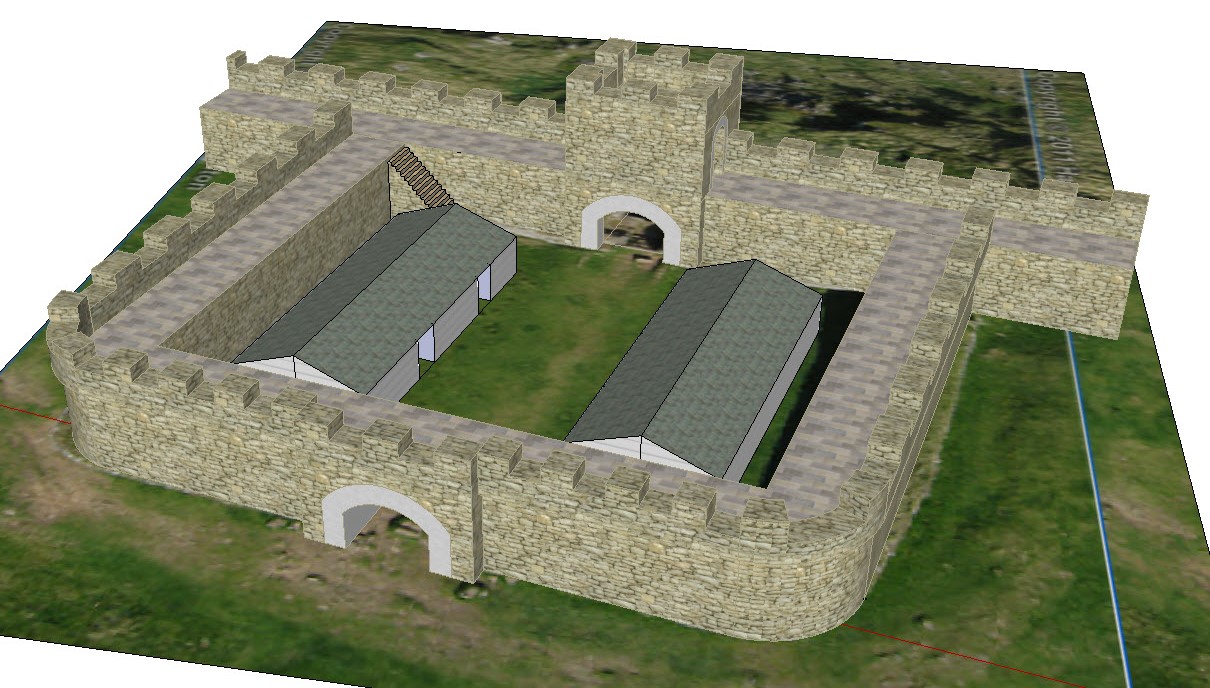

The chances of many plants colonising the walls whilst it was being maintained by the Romans is probably small. Back then the wall and the forts would have been covered with plaster and then painted quite brightly. It would not have looked like it does today. The locals might have described it as a bit of an eyesore across the beautiful Northumbrian and Cumbrian landscape but it was there to make a statement and painting it white and other bright colours certainly did that.

Some plants may have grown along the top, in between the cobble stones and down in the Vallum. However I suspect that maintenance was quite rigorous. The soldiers would have needed to be kept busy to prevent boredom and possible misconduct, so tasking them with weeding and repairs would be an obvious way to occupy them. I once recall seeing some squaddies at an army base in Cyprus mowing the playing field. There was not a blade of grass anywhere to be seen as it was dry bare soil but still they mowed up and down obeying instructions.

Colonisation probably did not get underway until sometime after 406AD when the Romans withdrew. Even after that date there is evidence that local rulers maintained sections of the wall and some of the forts for anything up to two hundred years. It would in any case have taken time for plaster to fall off and cracks to develop. The first colonisers would be plants dispersed by seeds or spores. Spores blow long distances on the wind and so mosses and lichens would be the first plants to show up, exactly as they do today on gravestones or rock -formed coastal defences. They would have paved the way for subsequent, larger species, as over time they died and got washed into the crevices between the stones so that gradually a type of organic soil would have developed. This would provide not only a source of water but also nutrients for the ferns and flowering plants that came later.

Ferns are also dispersed by spores and so the second wave of colonisation probably had a high proportion of ferns. Plants might also have arrived by way of animals bringing in seeds. Many species of plant produce fruits and nuts in order to attract animals which then either move the fruits and nuts to store them somewhere such as in a wall, or they eat them and the seeds pass through with their droppings and get deposited on the wall whilst the animal is having a rest.

However getting to the wall is just the start. The seedling then has to get established. In the Vallum this might have been quite easy and soon this would have been overgrown with Brambles, Hawthorn, Blackthorn and, probably Gorse. Thereafter trees such as Oak and Beech might have developed although the climate can be is quite cold and bleak so they would have struggled.

On the walls of the forts and along the wall, life would have been tough for the flowering plants. Plants that were already adapted to grow on rock faces and cliffs would have found the walls most suitable. The number of plants back then that could have colonised would have been significantly fewer than today. Well over half the plants that we now find on walls would not have been in the Britain at that time as they have been introduced since then. It is possible that soldiers might have brought a few species with them. Wallflowers are generally thought to have been introduced by the Normans but they do have lots of medicinal uses and conceivably soldiers could have imported them as it has been recorded that Roman soldiers used a poultice of Wallflower leaves to treat wounds. However most of the Roman soldiers stationed on the wall and in Britain generally were not from Italy. Many came from Gaul and two of the brigades that were stationed at the wall were from Tungria , now Belgium, and Batavia on the Rhine delta.

The flowering plants most likely to have colonised the wall would have been species such as Stonecrop, Whitlow Grass, Bittercress and Sandworts. These are all small native species which would not have made much visual impact.

As time went by the wall was gradually plundered to provide stone for other constructions, some of them, such as Hexham Abbey, quite grand, others less so. The B6318, known as the Military road which runs west from Newcastle, was constructed from stone which was removed from the wall and pulverised to provide hardcore.

Nowadays the wall attracts thousands of visitors each year and car tyres and walking boots will bring seeds from all over the world so who knows what could turn up. Getting there is just the start and colonising is the big ask but with climate change anything could grow there in the future. Perhaps there might be orange groves and olives lining the route one day. Very Italian.