I was unsure whether to include Buddleia as a wall flower partly because it is a shrub and partly because I was uncertain as to how often it grows out of walls. However as I have visited more and more walls I became satisfied that it qualifies as it is quite commonly found in walls. As for it being a shrub, I have noted that in many walls it is quite small and struggling and rarely reaches the size that it can do when growing directly from the ground. This may be because whoever is looking after the wall perceives that it could be causing substantial damage and removes it so that it never gets that big whereas a little bit of Rockcress or Ivy-leaved Toadflax just goes unnoticed. Consequently although it is a shrub plants such as Valerian are the same size or even bigger than the Buddleia. I have also chosen to include Ivy and Wall Cotoneaster and they too are classified as shrubs.

Network Rail says buddleia has a habit of growing in walls where it can interfere with overhead power lines and obscure signals. Whilst it does not cause “serious” problems such as blocking train lines, it does have a habit of popping up in “annoying places” where removing it takes up valuable time and resource.

The company cuts down large buddleia before removing or killing the stumps, sprays small buddleia with herbicide, and uses weed-killing trains to keep the network clear, while staff use portable sprayers at stations.

One would think that the potential for nuisance might be outweighed by the benefits to wildlife, such as butterflies.

Buddleia was imported from China in the 1890s. There are over a hundred and forty different species of Buddleia in the world. Its scientific name is Buddleja davidii which is a nod to Pere Armand David a Catholic missionary who worked in China. He is more famous for the Pere David Deer which he rescued from the brink of extinction by bringing some back to Britain where their numbers increased and then some were successfully reintroduced back into China. He also is responsible for introducing over 50 different Rhododendron species into Britain which as it turns out was not such a good thing.

Buddleia is the common name and Buddleja is the scientific name because Linnaeus, who was responsible for naming many species ,wrote his ‘i’ with rather a long down stroke so that it looked like a ‘j’ which caused confusion. It could have been called Buddleja davjdjj!

Buddliea is now considered an invasive plant although I would not put it in the same category as Japanese Knotweed or Himalayan Balsam. It gets about by virtue of its winged seeds so it spreads along railway lines quite well. It is recommended that one removes the dead flower heads before the seeds form thus encouraging it to produce more flowers but preventing the spread of the seeds. This is the strategy I adopt with the few bushes that grow in my wood. The flowers are out from June to October, It can grow into quite a large bush maybe 5metres high but in walls it is normally limited. Certainly at Chepstow Castle it was not very large.

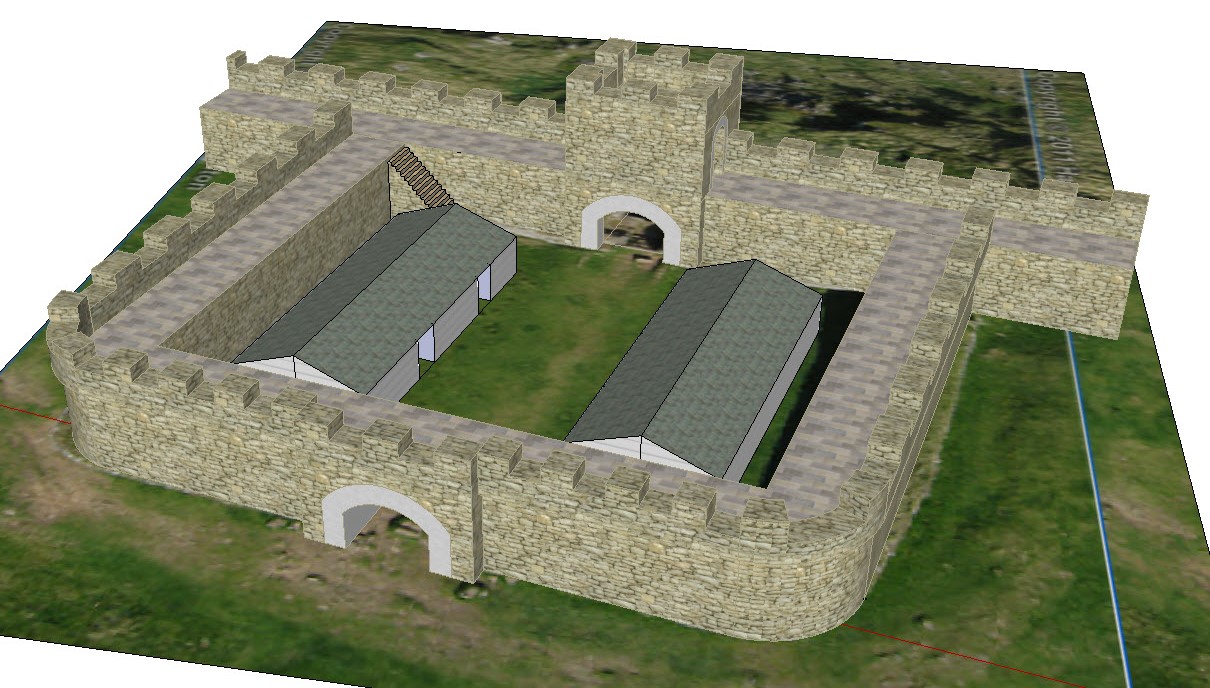

The castle though is quite impressive and has a good range of flowers in the walls as the maintenance is not over harsh. It is managed by Cadw. This is a Welsh word meaning ‘to keep’ or ‘to protect’ and that’s exactly what the organization does, working for an accessible and well-protected historic environment for Wales, so obviously the integrity of the walls is a priority but equally they are not over zealous in removing every fern and flower.

It did not take long after 1066 before the Normans set to work securing their new kingdom. Construction of Chepstow Castle was was started in 1067 by Earl William Fitz Osbern, close friend of William the Conqueror, making it one of the first Norman strongholds in Wales.

Later it was occupied and improved on by William Marshal (Earl of Pembroke). He was a very interesting character. He was originally just a small time knight but due to his jousting prowess he impressed Elanor of Aquitaine and subsequently her eldest son Henry II. As a consequence he acquired a French wife and the castle. On his deathbed Henry II asked William Marshal to take his cloak to Jerusalem, just a small trip but I suppose you did not argue with the monarch back then. On his return he was rewarded by Eleanor’s second son, Richard the Lionheart, who allowed him to marry the rich de Clare heiress Isabel. It was her family who had held Chepstow and other vast estates for most of the twelfth century. However the castle was in a bit of a state and so he set about doing it up and making it nice, a couple of extensions and maybe a lick of paint. Actually I find the the most impressive legacy of his works to be the double doors at the entrance. These have been dated using dendrochronology and found to have been constructed sometime before the 1190’s although the doors were once thought to date from the thirteenth century. This new information has established that they are the oldest castle doors in Europe. The doors which can be seen as one enters the castle are not the original doors. They are modern replicas but the originals are on view preserved from the elements inside the castle.

Richard, who, incidentally acquired the tag ‘Lionheart’ some years after his demise, famously spent very little time in England and it was William Marshall who ran the country for him in his absence. Other notables of influence who owned the castle over the years included Roger Bigod (Earl of Norfolk) and Charles Somerset (Earl of Worcester). They all made their mark before the castle declined after the Civil War. Roger Bigod was also responsible for the construction of Tintern Abbey, just up the road.